Darkness Falls: September to October of 1987

It's been a few years since Chicago Lakeshore Hospital closed down. I want people to know what went down in there and why it was called a "Hospital of Horrors" for countless generations of children and teenagers who were abused and neglected by everyone from the staff, to medical practitioners, to their own families. My experience was no different, but the kindness and compassion of a select few, including a gentle and soft-spoken NFL linebacker, helped strengthen my resolve to find a way out of there.

Darkness Falls

A chronicle from 10 September to 31 October 1987

Welcome to Hell. Turn BACK and RUN while you still can. Abandon HOPE all ye enter here... although I didn't.

There is nothing pretty to see here. It is a journey into the heart of darkness, not unlike Conrad's novel or Coppola's film. You might even call it my version of Dante's Inferno.

The move from the city to the suburbs was chaotic. My mother and I were left to do all the work on our own since my father was never at home during the day. I gave away my comic book collection to a young kid whose family had moved in below us and most of my toys went out the garbage, even stuff I'd still kept from our days in Spain. During our actual moving day, one box was left behind by the dudes my parents hired. I remember it contained my two metal lunch boxes from childhood, a Walt Disney World box from the 70s and a G.I. Joe one from 1982 that I'd only received from my mother a few years prior. They're both worth a pretty penny nowadays.

I wasn't nostalgic about leaving behind that old apartment on Ridge and Touhy in the least. My only regret had to do with a girl I liked in 7th and 8th grades who lived around the corner that I would never see her again. Otherwise, I took out every nail off my bedroom wall, even cutting off the handle from my closet lamp, which was tied to a string you'd pull to light it up. As far as I was concerned, anything that didn't come with the place was leaving with us. My father came back a few days later to return the keys and I was told by my mother that he lingered around a bit. Clearly, he felt different about our time there. Where he likely saw it as the start of his medical career, (and flirtation with womanizing) I only knew it as the place where my parents' marriage finally came unglued and where I had often contemplated suicide.

The movers made a right mess moving our stuff to the suburbs. They promptly scratched the wall leading to our bedrooms while hauling in furniture. It looked like Wolverine had clawed his way through it. As they trashed our belongings, my father gave me a look as if I was to blame, but said nothing. Soon as we had settled in Woodridge, we continued with the usual routine: I wouldn't see my father since he left for work before I got up, and returned after I had gone to bed. The arguments continued.

I don't remember anything from the last week of August through the first few days of September, but one morning while waiting for the bus on the first day of school, something snapped. I just walked away as the bus picked up the two other kids who were standing there alongside me. Somehow, I must have hailed a taxi cab into Downers Grove and gotten on a train headed towards the city. I dumped some fancy new backpack/briefcase hybrid that I was carrying to hold my text books in. Since I never got to school, it was probably empty. I think I just left it inside a wastebasket. (In the post 9/11 era, such an act might have gotten me arrested on the spot.) I then headed off into the streets of Chicago in a zombie-like state.

I walked through Michigan Avenue, down the warehouse district, then up by way of the Loop, and back to Union Station. Or something to that effect. I rode a couple of buses wondering if there was a form of suicide that was truly painless. I actually really wanted to develop wings so I could fly away because I didn't truly want to die, just for the pain and bad people like my father to go away. By the time I finally called home, it was nightfall and my parents had reported me as missing at the local police station. My mother brought along my middle school graduation photo for identification. The cops took it in stride, as did my father, who told my mother that "kids run away from home all the time." I took the train back and met up with them at the station. I gave them some cobbled up story about being mugged which nobody bought and by late evening, my father had called his shrink buddy in order to "register me for observation" at Chicago Lakeshore Hospital's adolescent psychiatry wing.

Sometime at this point, I asked my mother to let me know about a big secret she'd kept from me until "I was old enough to understand it." I couldn't feel more aged at that time, and I wanted to get any further traumatizing experiences over and done with. My money was on learning that I was adopted. Or (hopefully) that Manuel wasn't my father. That would have explained so many things. But a birthmark we both share on our right ankle made that highly unlikely. If it were the other way around, though, I would've have been devastated. No way would I ever accept that Gladys Castro wasn't my birth mother. Not that. Anything but that. We were too close, too damn close not to be tied by bonds of flesh and blood.

So what was the secret? Drums rolled: She had been married earlier on in life to another man. The guy had cheated on her. She was divorced when she met my father. With their sixteen-year age difference, it all made a sloppy kind of sense. She'd married in her forties during the late sixties and early seventies. That left the fifties to work with. They had no kids because the guy, one Hector Benitez, didn't want any. He's dead now, and I'm told he was mad as a hatter. A very tormented man who indulged in humiliating others, especially my mother. He'd tried to kill her on several occasions before dumping her at my grandparents without her knowing about it. I'm glad he's dead now because he'd asked her to forgive him after their divorce. Had we ever met later in life, I would have castrated the sorry fucker.

But that was it: She had been married to another dude who had been her teenage boyfriend. No biggie, it just meant that she'd slept with another man before my father came along. I could live with that. I'd have far bigger things to worry about the following morning. Horrendous, wretched, torturous ordeals at the hands of the most despicable monsters I'd yet to encounter in life.

On September 10th, 1987, I packed a few of my belongings and my father drove me there. He was amazingly relaxed. Even though the shrink, (who I'll call Rafael Carreira because that's his real name) assured me that "I'd simply watch TV in my own room whenever some specialist wasn't asking me questions to better help me improve my condition," I could tell that this was no ordinary clinic when I noticed an armed security guard standing by the elevator. The Hospital Director looked exactly like actor Jordan Chaney, who played Mr. Angelino on the TV sitcom comedy "Three's Company." But there was nothing funny about this particular bearded bastard. Right off the bat, he came off way too pleased to see me for someone who was supposed to oversee how his staff "cured" me of my illness.

Paperwork was done, my father said his goodbyes before promising to visit soon, and I was assigned a room. Turned out that I'd be sharing it. The second thing I found odd was that my roommate was wearing a robe over his pajamas around noon or so. He introduced himself as Tom. As someone brought us our lunch trays, Tom bluntly asked me why I was there. I told him and inquired as to his own reasons. "Oh yeah. Well, you see, I tried to kill my Mom again. I slapped her around a few times and got her by the throat. The bitch didn't take it too well this time and she had me locked me up in here. Can't say I blame her, since we've never really gotten along."

That was when I noticed that all our windows were locked and there were steel bars along with a screen behind them. And there was not a TV in sight. Carreira had lied his ass off. From the outside, it looked like the place had a sunroof. That was not a sunroof up there. It was a cage for teenaged humans.

This was in 1987. To give you an idea of how the place has "improved," I will quote from this Google review from last year, including its misspellings:

"I have been here twice for depression and it was horrible, the other patents where either homeless or just beyond help they stink and the place is always smells like pee, all the groups i went to where about drug usage and they never once gave me counselling about depression or anything that has to do with what was wrong with me they just prescribed pills and that is all, I came out of their the same as i came in they didn't help me at all! it's a horrible place don't come here."

The reviewer gave the place two stars.

Then, there is this one from ten months ago:

"I've been there 2 times it was horrible."

Again, two stars. These kids are likely young enough to be my children. The hospital is currently under investigations of allegations of child abuse on the part of both employees and fellow patients. But back in the Reagan era, the place came very highly recommended. At least to my father, given that Carreira sent all his teenaged charges there and the hospital director was a personal friend of his.

I had three roommates during my stay at Lakeshore. Tom, who was never allowed to wear his own clothes, came from the northeast. It amused him to no end how I would suck on the ketchup packs I was given since he heavily disliked the stuff. It was he who showed me the ropes, basically letting me know that there would be no TV watching (indeed, there was no set in any room) except during "communal time" between patients, that most kids only left after their parents' insurance had dried up, and that you couldn't check yourself out unless you were over eighteen years of age. Which meant that, much like the Eagles song, "you can always check out, but you can never leave."

Tom prided himself on being an expert manipulator, the word of choice among counselors and staffers for kids who wouldn't play nice during their stay there. "The really desperate ones get sent to the east wing," he said. "That's where they give 'em shock therapy." Early on, I watched as one kid was carted off in a hospital bed only to hear him screaming his lungs out as he reached the electroshock room. I was told that he was a junkie, but whatever they did to him in there would be of no help in the weeks to come.

Twice a day, you had group sessions where everyone was required to mouth off against a fellow patient by literally pointing a finger in his or her direction and letting the counselor in charge of the session know that Wally wasn't pulling his own weight or Sally wasn't putting in enough effort to improve herself. Basically, you were forced to snitch on someone you barely knew. Within the first few weeks, I had a meltdown during one of these meetings and ran away from the room screaming like a banshee.

My clothing privileges were revoked and I was soon relegated to pajamas and a robe just like Tom, who left soon after "reconciling" with his mother once more. "Next time, I'll make sure to finish her off and hide the body. Or we might make up and never fight again. Whichever comes first." Those were his last words to me before he left, with a literal wink and a dry "good luck" as he nudged me.

As for myself, things came to a head when my parents arrived one night to check me out, only for Carreira and the hospital director to block my release. That's when I figured that if everyone expected to deal with a lunatic, I would give them one. I lunged at Carreira and it took four or five men to subdue me. One of the counselors wore glasses and I slapped them off his face, something for which I later apologized. But I was in full-on berserker mode, crying and cursing and shouting and screaming my face off. It was the only time in my life that I called my mother a bitch. She sobbed like a newborn babe as my father led her away.

Having instantly gone from mere nuisance to Public Enemy Number One, I assumed that the electroshock room was being warmed up for me, but the insurance apparently didn't cover it, so I was tied hands and feet spread-eagled atop a bed in solitary confinement. I can't remember if they used the straightjacket on me before that, but I will never forget being tied to that infernal bed, looking out the bars on the window and wondering how I'd ever gone from a shy and withdrawn Catholic schoolboy to an alleged teenaged basket case within three years of arriving in Chicago.

Carreira walked into the room, a smirk on his face. He calmly laid down the law, saying that I had brought all this on myself and that it was imperative that I be "treated accordingly" if I was ever to be a "fully-functioning and productive member of society again." It sounded like he'd stuck me in a gulag, which wasn't that far off, except this was a capitalist gulag. I looked at him in the eyes and said. "If I ever do get out of here, I'll kill you." He just smiled wryly and shut the heavy steel door behind him on his way out.

Soon afterwards, whatever drug they gave me to calm my nerves did its thing. Having a clear mind always helps, as did the fact that most of the employees there were not bad sorts and were only doing their job. But they also said that at the Nuremberg trials, so who really knows.

One of the female counselors and/or nurses was a busty, good looking blonde with a very nice figure. In the midst of all that madness, she was the one person who reminded me that I was still a guy. She was also the only one out of all the women there willing to hug me, and if there was anything I was lacking in at that moment, it was physical affection. When the time came to feed me, she was given the task. She asked me to promise her that I wouldn't attack her if she untied one of my wrists and I assured her that I wouldn't. I wish I could remember her name. As I slowly brought the food to my mouth, she advised me: "Joe, you've got to learn how to get along better with others. I don't want to see you hurting like this because you're really a very nice guy." I thanked her for her concern but my response was "If I don't leave this place soon, I'll be dead far sooner." I don't think she felt that she had to tie me up again, so she probably left me to lie on my side facing the window until I finally got some sleep.

As an "uncooperative" patient, I was forced to sit on a chair they called "Chair," a plastic kindergarten one at that, in the middle of the hallway for everyone to see me as a form of public humiliation. I resisted the treatment, proclaiming that I was a man, not some moribund vegetable. (Patrick McGoohan would've been proud.) One time, I was left there for so long, that I lost my nerve again and lamely began stabbing my wrists with a plastic fork. Nobody noticed until I screamed "Fuck you all, I'm a goddamned human being! What kind of monsters are you to walk by and ignore me like some stray dog?"

There was a huge black dude there, a male orderly whose job was to "wake" up us everyday and march us off in a straight line to a series of small closets which served as the hospital showers. It was another communal shtick which they enjoyed doing to lower morale even further. This big oaf's method of choice in waking me up was to pull my legs out of bed while yelling "it's morning already, so move your fool ass!" He finally took note of me forking away in that chair and I was sent off to my room until more proper punishment could be dispensed.

Accordingly, I had been given a twice-daily cocktail mix of pills since the day I arrived at the place without being told what they were. You had to open your mouth afterwards to make sure that you'd swallowed the stuff. I'm positive that Carreira's beloved Nardil was in there, along with additional junk meds which they needed unwilling guinea pigs to test on. Within days, I was experiencing body cramps and uncontrollable muscle twitches. It was later diagnosed at Mercy Hospital as a "lite" or drug-induced version of Parkinson's Disease. My tongue was literally tied, something that horrified my mother when she and my father came to visit once. Carreira assured her that I was "faking it" because I was a sympathy whore. She brought things like chocolate chip cookies and comic books which were turned away because I was "dangerous" and "at risk of harming myself or someone else" so, no outside food or reading material for me. As if I could slit my wrists with a cookie or my throat with a page from a comic book.

My second roommate was a black kid named Eric. We didn't get along. He was not amused when I confused Michael Jackson's Bad album, (which had just debuted) with his hero LL Cool J's single "I'm Bad" (which was placing the up-and-coming rapper on the map at the time.) Eric also got little sleep after my continuing Parkinson's symptoms led me to throw up every evening right on cue around the wee midnight hours. This frustrated him to no end. Clearly, he was not a compassionate fella. But good fortune called and his parents decided to spring him not long after getting stuck with me. I remember him leaving sharply dressed and happy as a clam while I sat on the infamous "Chair" yet again. As the elevator doors closed past the armed security guard, I thought "well, at least that's another bastard who made it out of this hellhole."

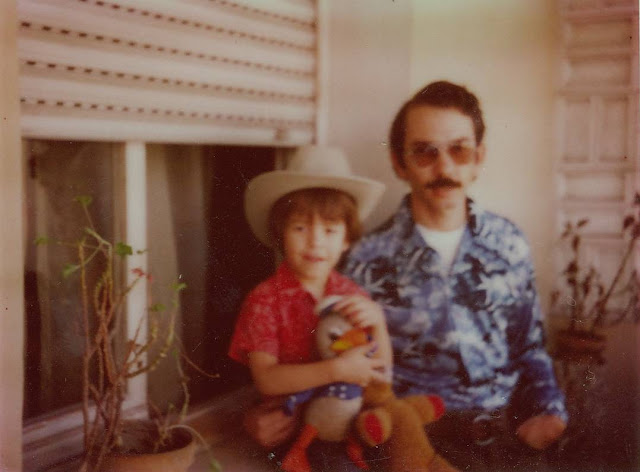

At this point, I need to mention Robert Thompson, a former NFL linebacker who had played for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and was serving as counselor during my stay at Lakeshore. He remains one of the few people I encountered who didn't kill off my faith in humanity at the time. But he didn't stick around long enough to see what would become of my situation, which was well beyond his control and for which I don't fault him. On the day he left to resume his football career playing for the Detroit Lions, he showed up in my room sharply dressed in a suit and tie. Kneeling by my bedside, he held my hand as I pleaded for him not to leave me. He calmly assured me that everything would be alright very soon. Robert was the only classy guy in that joint. He's got an entry on Wikipedia. That's Robert in the photo below. Go look him up.

Most parents didn't place their kids at Lakeshore out of parental concern over their welfare. I met a kid there named Tim who spoke with a lisp. He was very well groomed and quite educated. He said his parents took a yearly vacation in Paris and feared leaving him alone at home. Attempting to avoid a scenario right out of "Risky Business," they had the boy institutionalized because he was apparently problematic in school. I got to know him well enough to believe his side of the story, especially after meeting his parents one day. They seemed more interested in French haute couture than whatever torment their kid had been enduring at Lakeshore.

My last roommate was Scott, a surfer dude type with long blond hair who looked like he belonged in a metal band. Scott's birthday was on March 2, the day before my father's, but they couldn't have turned out more differently. Scott was older than me and his ultimate fate was a transfer to a reformatory in (if memory serves) the state of Maine, of all places. I never asked him why he was being treated like an outright criminal, mostly because whatever he had done didn't merit the punishment. I was told that it had something to do with drugs and/or petty larceny. Scott acted very maturely and looked older than his years. He was blunt: When I confided in him how good it felt to be hugged by the blonde counselor/nurse who was always nice to me, he laughed it off and said, "That's no big deal. She's fully stacked and you can feel her tits against you through her sweater whenever she hugs you so you're clearly enjoying the ride. You're just horny, that's all." I would smile and agree with his hypothesis.

But Scott was also very empathetic. One time, after my parents told me yet again that they couldn't take me back home, I sat in bed and wept to no end. Scott laid down his tough guy, metal rocker persona and hugged me like he was my big brother. He kissed my head and face in the manliest, non-sexual, most Christ-like way you could imagine because I was screaming my lungs out and nobody else gave a shit. I needed those hugs and kisses badly and he was there for me. I'll never forget him for his love and compassion, or for supporting me like nobody else had done in that infernal place. Wherever he is, may his God bless the guy.

One day, I looked out the window and spotted the junkie who had been given electroshock soon after my arrival. One of the counselors was a young guy, very mellow and well-meaning. I don't remember his name but we'll call him Mullet Dude for obvious reasons. (My mother once caressed his face because he looked so young that she mistook him for a patient.) The roof area had a sundeck which was (of course) also covered in steel bars so you couldn't escape through there, either. Well, the junkie tried it anyway by squeezing his skinny frame between two bars. I could see him losing his balance, his robe open and tears flowing down his face. He was just a scared little kid and yet, there he was, like a Jew running from his Nazi tormentors somewhere in Europe mere decades earlier. Mullet Dude risked his own life going after the kid over the oval bars, trying to reach his charge before one or both of them tripped off the roof to their deaths. I lost it completely and began crying as I watched the kid's eyes widen when he reached the roof's border. Scott pulled me away as I kept crying on his shoulder. Later on, we learned that Mullet Dude had caught the kid in time and pulled him back inside the building.

The sundeck also served as an impromptu gym and we were taken there late in the afternoon to play hockey (don't ask) or listen to records. That was their idea of "therapy" but all we cared for was getting some fresh air and seeing the sun shine in. The cafeteria was also located there. I grew to despise waffles with a passion since that was basically all we were given for breakfast. The lunch menu mentioned sandwiches with a side of "french fries" which turned out to be canned shoestring potatoes, the kind you always see next to the the peanuts at your local grocer's snack aisle. One of the counselors was downright batshit crazy and he insisted that whenever we walked up the stairs to the cafeteria, we should not avoid any steps because "we would hurt their feelings."

By this time, we were deep into October and I had no idea of what was happening in the outside world. Was Reagan still president? Did the new TV season suck or not? Had "Married ...with Children" been renewed for another season? (I had a huge crush on Christina Applegate!) One day, someone decided that kids our age were supposed to be attending high school, so we were given a tutor to give us language, math, science, and reading lessons. I welcomed those sessions because they made me feel more like a normal kid again, although my math and science skills sucked in captivity much as they had in freedom. My health condition had also seriously deteriorated to the point where my mother couldn't understand what I was saying most of the time. Neither could Scott, but he knew the kind of junk I was getting pumped into my nervous system. He regretted not being able to testify against Lakeshore and Carreira because he was soon being shipped off to the reformatory in Maine.

My mother was at wits' end by then and threatening my father if he did not try harder to have me checked out of the hospital. My father, in turn, gave me a sob story about his running the risk of "being sent to prison" by the health insurance company if I left the hospital "before January," which was when the policy expired. Then as now, I had no fucking idea what he he meant by that except that it was utter bullshit. Eventually, I developed a sharp pain in my side which someone feared might be appendicitis. An outside physician was brought in and he checked me out. The Hospital Director was present. The physician was worried about a series of scars on my back which looked more like stigmata, but I feared that he would think that my parents had been physically abusing me. If he blabbed about my scars and interpreted them as whippings, I might have never left that place. But luckily, his main priority was to decide whether or not I had appendicitis. Since The Director was a friend of Carreira (and equally benefited from my imprisonment) I limped as badly as I could in front of them, moaning in pain to make things look authentic enough for the outside physician to worry.

Somehow, by some act of divine intervention or sheer blind luck, my bluff paid off! The physician had noticed my shaking and speech impediment but mostly worried about the possibility of appendicitis. Or maybe he caught on? If he'd checked the med list I was on, he would have called everyone out on their use of Nardil. In any case, he suggested that I be taken to Mercy Hospital for lab exams. Carreira and The Director weren't too happy about that but it was finally out of their hands. On the afternoon of October 27th, I was called out of my science lessons because I had a "visitor." It was my father, come to drive me over to Mercy. I thought he was messing with my head again, but he said "get your things, I'm getting you out of here because you need to get checked out." For a moment, there WAS a God. I told Scott and he helped me gather my stuff. We said our goodbyes and wished each other the best of luck. I packed up my gear.

Most of it anyway. The hospital kept (and promptly lost) things such as my old hairbrush, which I'd grown attached to over the years and felt bad about losing. After all I'd gone through, I didn't want to leave a single personal object of mine behind in that hellhole. A close analogy could be made by comparing my hairbrush to Wilson the volleyball, Chuck's companion in the Tom Hanks film "Cast Away."

My father and I walked past the armed guard as the elevator opened. As I walked out the automatic front doors, I remember The Director joking to my father about "remembering to bring me back" after the exams were done. With my stare alone, I cursed him and whatever brood he spawned throughout his next fifty generations. Weeks later, he would be denying everything that had occurred under his watch, claiming that he had "no idea of what went on between the staffers and patients" and that he "could not be held accountable for any prescription discrepancies issued by my doctors." I sincerely hope he roasts in Hell, if there is a worse one than the barren pit he so gleefully supervised. In any case, I had seen the last of Chicago Lakeshore Hospital and was admitted to my father's workplace, Mercy Hospital and Medical Center.

On the way to Mercy, I looked at my father and stammered my words until I said: "You better damn well know I'm never going back there. I'll jump out of this car first." My father was stone faced throughout the ride. He replied: "If this all pans out, you won't have to."

I spent the final week of October or the last five days at least, at Mercy's adolescent wing. I was taken off the psych meds and the trembling and twitches finally stopped, but then my muscles began to hurt like the Cubs and White Sox had collectively beat the living shit out of me with their baseball bats. This was actually a relief for me because it meant that my body was returning to normal. I regained the ability to speak properly and answered the doctors' questions. I did find it difficult to sleep at night because a nurse would walk in at any given moment and pop a tube in and out of my ass. I was in a haze but realized that I was being given enemas to flush all that chemical poison out of my system. Eventually, they had to downright pump my stomach out. My father said that it was mainly to make sure that it wasn't appendicitis. He was there for the procedure and I remember saying to him: 'Hey, hold my hand at least, will ya? You're only my freaking father, for God's sake! I need your support." He grabbed my hand and held it for the procedure's duration without smiling at me even once. I think he wanted me to die somehow. I was nothing but a nuisance for him at that point in our lives.

I became friendly with the elderly nurse in charge of the wing and she gave me carte blanche to use the phone. I talked to my mom, I called Anaheim to tell my grandmother and aunt that I'd be fine, and I called Arnaldo Ruiz, the guy I loved most and who was my lifelong mentor. He and his wife had been in touch with my mother throughout the whole ordeal. Two or three times a day, my father's colleague Alberto Betancourt would stop by and visit me during his breaks. I was overjoyed to see him again. I told him, "Alberto, I thought I'd never survive that place. I'm going to live every day as if it were my last and the first thing I want is women! Can you get me women?" He laughed, and leaned back in his chair, replying: "Well, I'm not sure if your mom would approve!" Then I pleaded with him in jest: "At least be a pal and smuggle the latest issue of Playboy in here. Can't you do that for me?" He kept laughing and said that my mom wouldn't approve of it either. He never met my mother but was very respectful of her. Despite feeling happy for me, he was cautious about my new-found freedom. "If by any means you have to go back there, I want you to be brave," he said. "Don't worry," I told him. "After they're done examining me here, I can guarantee you that I won't be going back there ever again."

The next day, My father entered my room accompanied by the two doctors who had examined me over the previous days. They were Polynesian or Filipino, or maybe they were Hindu. I don't remember which, but I will never forget their words...

"You're lucky to be alive. A few more days in that place and those pills they had you on would have surely killed you. A kid your age can't be prescribed the sort of stuff they had you on. It's a criminal offense." They spoke of heart failure, the Parkinson's effect, the twitches and convulsions, the vomiting and dehydration. Of how I'd barely made it by leaving when I did. I looked at my father, expecting an emotional reaction of some kind. He just stood by the window in his white coat and calmly looked out into the distance.

I thanked both doctors profusely for saving my life. Betancourt stopped by to congratulate me with a genuine expression of relief on his face. Surprisingly enough, Carreira showed up as well, but there was nothing pleasant about his appearance. I'm pretty sure that he cajoled my father into letting him get the last word in. Half grudgingly, he sat down by my bed and said to me: "You're getting away with it now, but let me tell you this: I'm never wrong in my prognosis. You're a sick boy and you will never be able to put two and two together and get four." (I will admit that in time, I was diagnosed with a math learning disability, but that wasn't his point. His point was that he never wanted my nightmare to end. He was right and I was wrong and that was the only way it could be for him because he never lost.) I didn't bother with a reply, but my father looked on approvingly as Carreira gave me one last "this isn't over" look before leaving.

Carreira was the sort of man whose children took off his shoes for him when he arrived home from work and put on his sandals. That type of guy. His father died before the year was through and he had the gall to send us a Christmas card after the Mercy team who examined me had yanked his chain. The Director had seemingly freaked out and blamed everything on Carreira. Manuel promptly broke off their friendship and asked my mother if she wanted to sue both him and the Lakeshore people, but my mother thought I'd had enough for a lifetime. Putting me on the stand so we could collect money wouldn't take away the pain. In retrospect, I would have indeed gone on the stand if it meant barring Carreira from the medical field along with his cronies and hopefully sending them to prison so they could have a taste of their own medicine. Even perhaps, getting Lakeshore shut down before further generations of kids suffered the kind of abuse that I endured. The passage of time has shown that none of the guilty parties learned their lessons. Carreira went on to experiment with the inmates at Joliet State Prison before returning to his own practice in adolescent psychiatry.

Rafael Carreira went to meet his maker on July 27th, 2022. His obituary noted his "compassionate dedication to those with mental health challenges" among other accolades. Yes, it's over, you goddamned son of a bitch. I may have turned out to be the failure you cursed me to be, but I outlived you in the end. The world is finally rid of your sadistic evil and I am a happier man for having learned of this fact. May your God judge you for every life you ruined throughout your miserable lifetime.

I was discharged from Mercy Hospital on October 31th, 1987. I had spent four days there. It was Halloween and my mother's 58th birthday. For a month and a half, she had been taking a cab to the train station, a train into the city, another cab to a McDonald's, and then patiently waited for my father to pick her up there so she could visit me. One time, she returned home on her own and was so depressed that she became distracted and missed the train stop at Downers Grove. Now, the nightmare was finally over for her as well.

My father's only words to me on the way home were: "Well, I hope this has taught you a lesson." In a way, it did. I learned not to trust authorities simply because they acted like they knew better than me. I also realized that given a choice, my father would rather side with the devil than stand by his own kid. I learned that he was a far greater coward than I ever imagined, and how this would all come to haunt him nearly thirty years later when the U.S. government attempted to land his own ass in jail for income tax evasion, health care fraud, and general corruption. He would do everything in his power, including lying through his teeth and tearing his family apart in order to avoid the hell I went through because he could never deal with being locked up the way I did. He's been a fucking piece of shit since the day he was born, and he will continue to screw people over for his own benefit until he is finally dead and buried.

But on that Halloween night, we called a truce. My mother played "Hallelujah" off a tape recorder (her choice of music) and kept our parakeets awake long enough for me to see them. I would make it a point of having them run free inside the house from then on whenever my father wasn't home, so their cages were mostly for sleep or travel. In my bedroom, my mother had been stashing everything she'd bought for me over the time I was gone: Letters from my family welcoming me home, mail order catalogs, a stack of comic books and Rolling Stone magazines, (but sadly, no Playboys) the 1987 Fall Preview issue of TV Guide which I'd asked her to get for me, (she bought and kept every issue while I was away) a couple of Hall and Oates cassette tapes, (my poster of the musical duo had "kept her hopes alive" whenever she looked at the front of my bedroom door) the boxes of cookies that had been rejected at Lakeshore, (Nabisco's Chips Ahoy!) and anything else she could throw in that she knew I'd like.

As stated, a poster of the rock/soul duo Daryl Hall & John Oates hung on my bedroom door throughout my absence from home. My mother had been initially intimidated by them, since they were the first things she saw after stepping out of the bathroom, but she grew to feel comforted by the two young men during the many nights she spent alone and grieving throughout our crisis.

The feeling of being back in my bedroom, (which I'd only slept in for a few weeks after our move to Woodridge) stays with me to this very moment. How best to put it into words? I was reading about Frederick Douglass' escape from slavery the other day, and this is what he had to say:

"I have often been asked, how I felt when first I found myself on free soil. And my readers may share the same curiosity. There is scarcely anything in my experience about which I could not give a more satisfactory answer. A new world had opened upon me. If life is more than breath, and the 'quick round of blood,' I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life. It was a time of joyous excitement which words can but tamely describe. In a letter written to a friend soon after reaching New York, I said: 'I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions.' Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be depicted; but gladness and joy, like the rainbow, defy the skill of pen or pencil."

That's more or less how I felt being free at last, in my own home, in the safety and intimacy of my bedroom. Even so, I was haunted and traumatized by the things I had experienced over the next year or two. At times, I would be sitting in our backyard and a terrible feeling of dread would wash over me, almost like I feared that Carreira and his Lakeshore goons would drive up to my house and kidnap me, not unlike that old butterfly net routine you still see in old cartoons from time to time. I had a lot of trouble dealing with authority figures for some time after, including cops, teachers, school counselors, and politicians. In time, these fears subsided and my normal, straight-laced, introverted personality slowly made its return. But the anger and outrage has never left me, and at my age, (I'm pushing 50 as of this writing) I doubt that it ever will.

In the end, though, what mattered was that I survived. I'm pretty good at that. Not long after I had returned home, my mother and I watched an episode of "21 Jump Street" featuring Johnny Depp and guest-starring Christina Applegate, which eerily paralleled the events that transpired at Lakeshore, except that the bad guys went to prison at the end. (Christina played a patient not unlike the few girls that I met at Lakeshore, most of whom were seriously messed up.) In the weeks and months ahead, I often played a song by the British rock band Level 42 which began to bring peace to my soul. Aptly titled, "It's Over," it served as a proper coda for my healing process.

The following summer, I remember watching the video for the new song "Perfect World" by Huey Lewis and the News on MTV at my grandmother's apartment, on her vintage console TV, in her living room. I thought back to everything I'd endured and felt like I had come around full circle. Much like Huey, I'd learned that the world wasn't perfect, but I was happy and relieved to be still alive and in it. And grateful that I was watching the newest video by Huey Lewis and the News on my grandmother's vintage console TV, in her living room. Her apartment had been the only place where I could find respite, going back to the day my mom and I first stayed there when I was but a mere toddler, in 1973.

Despite Thomas Wolfe's old adage, there's a lot to be thankful for in regards to consistency. At age 15, I discovered that it was still possible to go home again.

Chicago Lakeshore Hospital closed down in April of 2020 after years of "allegations of sexual assault and abuse of children there, as well federal and state inquiries into safety violations. The Chicago Tribune separately reported on troubling conditions at the hospital."

*

09/17/2022 Postscript...

It reopened in 2021 after Big Med Conglomerate Acadia Healthcare sank its claws into it. They renamed it Montrose Behavioral Health Hospital and it is set to doom further generations of innocents, from childhood well into their geriatric years. If they even make it there. Acadia trades on Wall Street through Nasdaq, so you know they're gonna want that place full of guinea pigs once again.

Because evil ALWAYS wins. Damn this world and "humanity" itself! Damn it all to Kingdom Come!

Comments

Post a Comment